WAR!

Enough with Politics, History, Art, Philosophy, Memoirs; Time for Some Interesting Funfacts!

We go off to wars

Settling many scores

But with little fuss

Scores will settle us

The study of war is both fascinating and time-consuming since, as a human enterprise, it requires learning, knowledge, critical thinking and an omnibus intelligence beyond the grasp of most of us. So to get to the meat of it, let’s simplify.

Large groups—nation states, assemblies of countries, corporations, mobs, boys clubs, cartels, all go to war to either get something or prevent others from taking what they already have. In simpler times, as was demonstrated in the opening scenes of the film 2001: A Space Odyssey,[i] a mob of proto-humans confronts another mob of proto-humans intent on absconding with the first mob’s provisions and, presumably, females. However, unknown to the attacking mob, the defending mob had discovered the utility of animal femurs and other large bones as weapons, and lo, humanity arises to ascend to the stars.

Principle, the first: they who have superior weapons will be victorious.

Yes, but as is true of all principles, it is not absolutely true as Custer discovered at the Little Bighorn, June 25-26, 1876. And while the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes taking part in the battle had the numbers if not the repeating rifles, we must reluctantly accept that victory requires more than blunt force.

We come to Principle, the second: they who have superior tactics will be victorious.

This assertion requires an example. In the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic eras—the Stone Ages—weapons technology advanced to the production of ever more sophisticated arrow and spear heads leading to the earliest organization of groups of citizen formations as cultivation replaced hunting and gathering enabling ever larger groups to establish more sophisticated farming communities to provide the means for uniting villages into towns and, ultimately city-states. This gave way to the early Bronze Age and the production of standardized weapons to supply armies capable of foraging afield.

In this era, while it is interesting to speculate on Stone-Age armies being massacred by better equipped Bronze-Age forces, history provides no examples. In any case such a fanciful confrontation is unlikely since the manufacture of bronze weapons requires a level of organization and technology well beyond the capacities of Stone-Age communities. It’s more likely that the change from Bronze to Iron weapons provides a more reasonable example.

In the interval 1200-500 BCE (depending on where in the world we look) Iron took command and this may be one factor among many contributing to the demise of the Hittites and Mycenaeans and the ascendence of the Assyrians.[ii] While there is much to be learned from the rise, fall and reassembly of the early Egyptian dynasties and the wars between Sparta and Athens, for the sake of brevity I will jump into the Punic wars and the oscillating risings and fallings of Rome and Carthage.

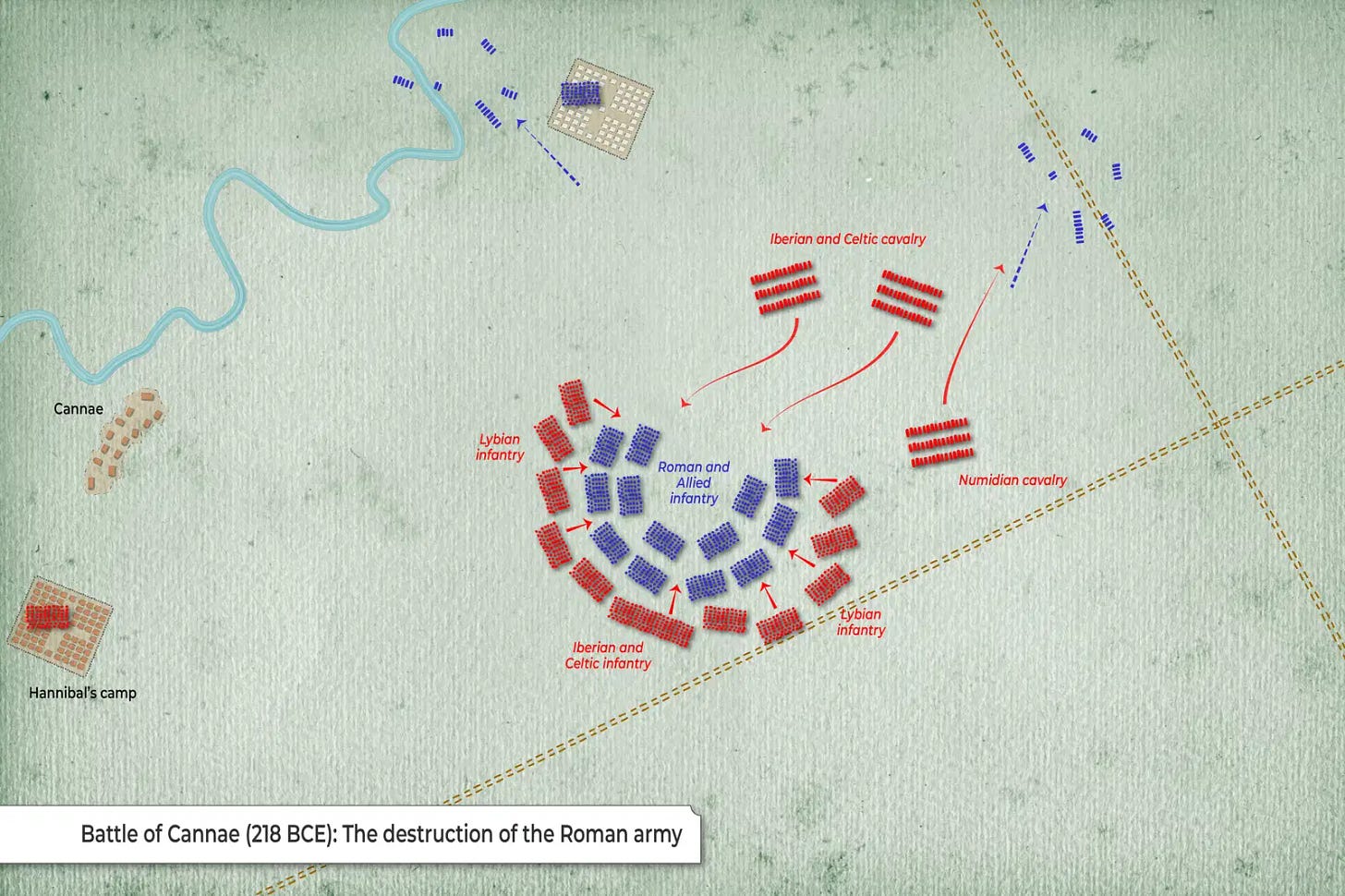

Specifically, the one battle that quickens the heart-beat of every would-be commander of armies; The Battle of Annihilation at Cannae August 2, 216 BCE during the second Punic War in which a Carthaginian force of 50,000 including African, Gallic, and Iberian soldiers under the command of Hannibal defeated a Roman army of 86,000 troops led by Lucius Aemilius Paullus and Gaius Terentius Varro. Somewhere between 55,000 and 70,000 Roman troops were massacred in contrast to from 5,700 to 8,000 Carthaginian losses.[iii]

In the history of warfare, this battle is an ineluctable example of superior battlefield tactics carrying the day. This begs two important questions: What are tactics? How do tactics amplify the strengths of the victor by exposing the weaknesses of the vanquished? On paper it is easy to explain what happened and why. But what prompted Hannibal to design this specific order of attack?

Hannibal was obviously facing a numerically superior force, a highly trained and seasoned army of veterans, well-armed and supported, aggressive and experienced in battle. Hannibal’s army was also experienced but more heterogenous drawing on recruits from North Africa, Iberia and Europe. But Hannibal knew well the nature of his enemy. He was aware that the Roman armies were habituated to ruthless tactics that sought to overwhelm its enemies by exploiting any weaknesses that presented on the battlefield. He purposely thinned the ranks in the center of his army, placed his cavalry and more heavily armored troops on his flanks and invited the Romans to attack his weakened center. As his center formations began to yield to the Roman legions, his flanking formations moved forward forming a bowl of armed men into which the Romans rushed. As Hannibal’s flanks moved forward, the Roman formations were increasingly crushed into the bowl that Hannibal prepared, gradually enveloping the mass of the Roman army.

Unable to maneuver in the concentration of soldiers accumulating in Hannibal’s trap, the remaining troops and cavalry of the Carthaginians encircled the hapless Romans and slaughtered them. It didn’t matter that the Carthaginians were an invading army seeking to redeem its defeats in the first Punic War or that the Romans were defending their territory, Hannibal, recognizing Roman tactics and propensities improvised a faultless plan to counter the likeliest movements of his adversary.[iv]

The real lesson of Cannae is that one commander, Hannibal, learning from his father’s failure to conquer Sicily in the First Punic War, engineered one of the most daring campaigns in history, invading the Italian peninsula through the “impassible” Alps, and scoring enormous victories in the battles of Trebia, Lake Trasimene, and Cannae, almost bringing Rome to its knees. To no avail. Hannibal was eventually defeated, Carthage and its client states forced to submit to a triumphant Rome that would go on to rule much of the world for the next eight centuries.[v]

Rome’s military commanders would learn from Hannibal that tactics on the battlefield required a thorough knowledge of your enemies.

Principle, the third: you must not only painstakingly study and understand the likely actions and responses of your adversary, but you had better understand and adjust your own actions and responses to guard against complacency in the wake of a victory that inevitably precedes defeat.

This is all well and good but it ignores the encyclopedia of factors that mold all battlefields and outcomes such as logistics, intelligence, strategy, alliances, resources, weather, politics and the human propensity to ignore the obvious.

But central to all failures in human conflict is self-inflicted illusions and a reluctance to study your opponent, the logistics, intelligence, strategy, alliances, resources, weather and politics opposing you. A failure, unfortunately, that Americans seem to have mastered in all its wars, only to be saved at the last moment by the time it takes to recover. Unfortunately, it is likely that in our current era we are running out of time.

All generals, dictators, kings and oligarchs fail with the possible exception of Alexander the Great who died before the collapse of the empire he founded; Hannibal at the Battle of Zama (202 BCE), Julius Ceaser at the Battle of Gergovia (52 BCE), Richard the Lionheart at the Battle of Jaffa (1192), Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle of Leipzig (1813) and at his final Battle at Waterloo (1815), Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg (1863), Erwin Rommel at the Second Battle of El Alamein (1942), and countless others.

In the wake—but not necessarily because of these military failures, empires fall. The central cause of such collapse is the drive of empires to remain ascendent as The Force Majeure in world affairs, through the imposition of military, economic and political force to compel the submission of neighboring states.

The glaring example is the Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) fought by Sparta and Athens and their allies. The initial phases of the war favored Athens, whose navy, land defenses, and alliances thwarted Sparta’s superior land army.[vi]

The central element leading to the ultimate defeat of Athens is the increasing authoritarian militancy exercised by Athens over its putative allies. The collection of neighboring states had entered a mutual defense pact with Athens called the Delian League. Well before the start of the Peloponnesian War, Athens forced the League into its governing orbit and exacted tribute from its members. The League’s treasury was appropriated in 454 BCE and Athens demanded recurring tribute. Athens then instituted a system of military garrisons and regime change to insure compliance. When revolts broke out, they were violently suppressed, most notable was the attempt by Mytilene in 428-427 to defect to Sparta. Athens crushed the revolt and killed over 1,000 deemed as instigators. Melos in 416 rebuffed Athenian demands and Athens retaliated, killing its men and enslaving its women. Athens essentially estranged its allies, assuring their lack of enthusiasm to come to Athen’s defense in her war with Sparta.

At the height of the war, Athenian Democracy was overthrown by the oligarchical party during a time of political turbulence in 411, 20 years into the war. And while the Athenian navy, refitted and able to win victories against Sparta and their Persian allies, had forced the removal of the oligarchy, the democratic rulers failed to reverse the more disastrous decisions of the oligarchy and eschewed negotiations to end the war with a more compliant Sparta then on the verge of defeat. The turmoil proved fatal. Without unity of command or purpose, Sparta seized the initiative and subdued Athens when in 405, the Spartan fleet, supported by Persia, blockaded Athens into submission, bringing an end to Democracy in the Peloponnese.[vii]

If this narrative has a familiar ring, then it is probably because we are stuck in the cracked groove of a record, hearing the same track repeating over and over.

[i] Kubrick, Stanley, director. 2001: A Space Odyssey. Produced by Stanley Kubrick; screenplay by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke. Warner Home Video, 2001.

[ii] William Schulz, THEORY TO EXPLAIN THE INTERCONNECTEDNESS AND DEMISE OF THE MYCENAEANS, HITTITES, AND NEW KINGDOM OF EGYPT, https://www.academia.edu/33161446/THE_BRONZE_AGE_COLLAPSE_IN_THE_AEGEAN_AND NEAR_EAST_USING_THE_GENERAL_SYSTEMS_THEORY_TO_EXPLAIN_THE_ INTERCONNECTEDNESS_AND_DEMISE_OF_THE_MYCENAEANS_HITTITES_AND_NEW_KINGDOM_OF_EGYPT

[iii] Gregory Daly, CANNAE: The experience of battle in the Second Punic War, Routledge, the Taylor & Francis Group, 2002.

[iv] Map: Battle of Cannae (216 BCE) – Deployment & Initial Attack, provided by TheCollector.com

Map: Battle of Cannae (216 BCE) – Deployment & Initial Attack provided by <a href=”https://www.thecollector.com/”>TheCollector.com</a>

[v] Dexter Hoyos (Editor), A Companion to the Punic Wars, Wiley-Blackwell, February 2011.

[vi] Donald Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, Viking Press, 2003.

[vii] https://www.britannica.com/event/Peloponnesian-War

I’m an ardent listener to these comments from deep thinkers.

Great fast walk in ancient military history. In my time in Italy on the north shore of Lake Trasimene you can still find artifacts of the battle, most of which are housed in a small museum on the site.

I had a similar experience in the wetland forests near Detmold in Germany where Arminius destroyed a Roman Legion. In the midst of the forest there is a giant monument of Arminius that was erected after the Franco Prussian War. He faces France with sword drawn. My German colleague who took me there said the space at the foot of the statue was Hitlers favorite spot for speeches in the run up to the war

During WW II a tank battle there churned up bones and Roman equipment.